In recent years, securitisation discourses have shifted the framing of migration as a human rights issue bound up with Cold War politics, to an issue of criminality and the fight against transnational organised crime. This has, in turn, led to an increasing overlap between criminal law and migration management at the transnational level in the European Union (EU) which is reflected by the increase in legislation governing the movement of people. Nothing reflects this phenomenon more clearly than the cases of strategic litigation brought against people-on-the-move (POM), and the lengthy prison sentences that accompany them. The criminalisation of movement in general has been in the focus of the Border Violence Monitoring Network’s (BVMN) advocacy work since its conception in 2017.

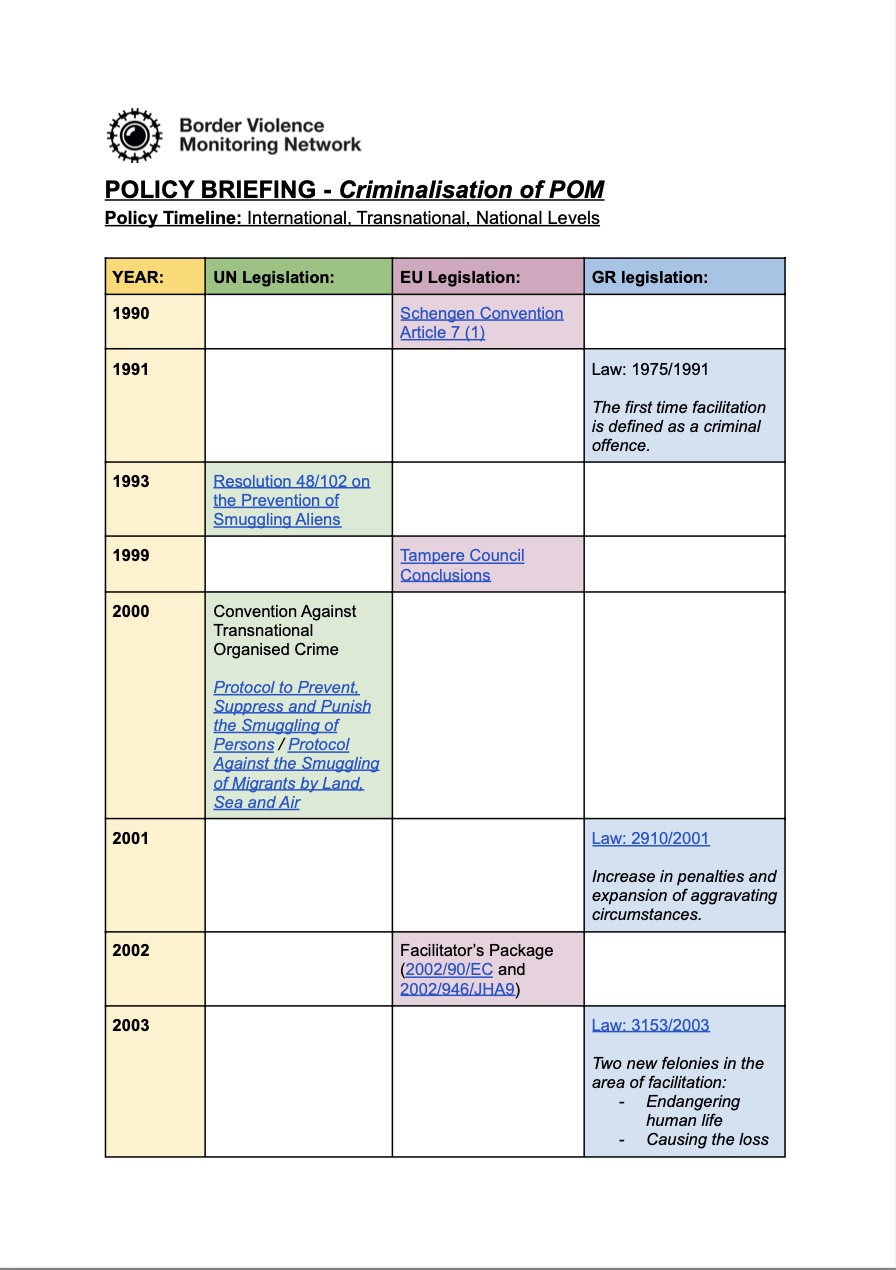

When analysing the relevant policy documents provided in the timeline above, there is a clear distinction between international human rights instruments at the UN level, and the ways in which such rights are provided for in EU legislation. In 2000 when the UN established the Convention Against Transnational Organised Crime, ratified by all EU Member States (MS), there was a clear emphasis on dividing the definitions and charges of ‘smuggling’ and ‘trafficking’ through the establishment of two separate protocols. Furthermore, the former protocol clearly outlined the rights of POM being smuggled and prohibited the criminalisation of individuals who were subject to smuggling. At the EU level, the distinctions between smuggling, trafficking, and illegal migration are ill-defined. The creation of an internal free market and free movement as put forth by the Schengen acquis required, inter alia, a commitment to strengthening the EU’s external borders as a means of protecting the internal body of MS. In fact, the offence of facilitation of illegal entry is first mentioned in Article 7 (1) of the Schengen Convention (1990). In 2002, the Facilitator’s Package furthered this agenda by putting forward the goal of the Commission to combat both illegal migration and the aiding of illegal migration. The package even stands in direct contradiction to the UN definition of smuggling; it doesn’t consider financial gain as intrinsic to this definition, simply an aggravating circumstance. Again, the mechanisms behind this are somewhat blurred with the terms used in the policy document such as ‘smuggling’, ‘financial gain’, and ‘humanitarian assistance’ left open and undefined, with full discretion being left to MS to decide how sanctions are transposed into national legislation (Article 3).