From Transit to Containment: How the EU Pact Lands in Serbia

By Stevan Tatalović, Program Director at Info Park, migration researcher and activist. Published on 25 November 2025.

Header image: Group picture of EU leaders at the EU-Western Balkan Summit, in December 2023. Credit: the Audiovisual Service at the European Commission

This piece was co-published with Statewatch.

It was almost dawn in the middle of summer. After a successful attempt to cut dents in the fence at the Hungarian border and climb over, a group of five individuals believed they had finally made it. But within minutes, Hungarian police rolled slowly across the field. Torches, flares, and spotlights weren’t needed; two buzzing drones had already marked their presence in the early morning sky.

The group of five was taken in. Days later, they shared this testimony with us at Info Park in Belgrade, repeating the same story they had already told four times that month.

According to them, what followed is what many on the route now call “babysitting”. Hungarian police phoned their Serbian counterparts: “They are all yours.” The group was handed over, packed into a windowless van, and driven for hours, sometimes for so long the sun would set before they arrived.

Eventually, they found themselves in the Preševo valley, inside a former tobacco factory repurposed during the so-called Syrian migration crisis into a camp that can hold thousands. No asylum procedure awaited them there, only exhaustion. Within two days, they had pooled together 600 euros for a taxi back to the Hungarian border, ready to try again.

A view of Preševo valley, as seen in August 2013. Credits: Julian Nyča

Governing the Route

The EU and its agencies often talk about the Western Balkan route as if it were a fixed corridor to be managed. But Info Park’s daily work shows how ill-fitting this description is. People’s journeys are rarely linear. They move forward, stall, retreat, or shift sideways depending on weather, money, smugglers, or police violence.

In August 2025 alone, we met 44 unaccompanied boys in Belgrade, many of whom had already been pushed back multiple times from Hungary, Romania, and Croatia. As one Syrian teenager told us: “Every time I think the route is finished, it starts again. I don’t know where the route is anymore.”

Critical migration research warns of this simplification: routes are not natural highways but co-produced assemblages of fences, smugglers, visa regimes, border technologies, and migrants’ tactical decisions. For policymakers, a route-based lens may help map flows. But for people on the move, the “route” is a revolving door of capture, dispersal, and regrouping, between pushback sites, police vans, and transit camps.

Our assessments confirm it: between May and August 2025, most new arrivals in Serbia had already been through multiple detours: first Greece, then Bulgaria, then circular pushbacks from Romania or Hungary.

“Managing migration” has become the catch-all euphemism in Brussels and across the international community. It is what donors and consultants say when asked how millions of euros are poured into fragile and often corrupt systems in the Balkans. If pressed to explain accountability, they simply reply: “We are managing migration.” But managing what, exactly? And for whom?

On the ground, so-called migration management looks very different. It is police raids in Subotica’s forests, the “babysitting” handovers at Horgoš in Hungary, and the endless transfers to Preševo. It is boys on the move asking our staff if their rights exist, while smugglers raise their fees and bundle services like transport, accommodation, and debt collection. In this sense, “management” is less about governance than about containment without responsibility.

Members of the Hungarian Defence Force install barbed wire on the Hungarian-Serbian border near Kelebia village in Hungary in August 2015. Credit: Freedom House

Mixed Movements, Blurred Categories

Another staple of migration governance is the concept of so-called mixed movements, where asylum seekers, refugees, and economic migrants use the same migration routes but for different purposes. The term seems neutral, but in practice it often produces hierarchies of deservingness.

We see this every day at Info Park. A Moroccan boy who fled poverty may be dismissed as an “economic migrant,” even if he endured violence and exploitation similar to an Afghan peer sometimes recognised as an asylum seeker. A Ukrainian family struggling with poor parental capacity is processed differently than an Egyptian unaccompanied boy, though both cases raise child protection concerns. And many people shift categories mid-journey: first seeking work in Turkey, then claiming asylum in Serbia, then rejoining family in the EU.

These categories are fluid, context-dependent, and politically contested. Yet they continue to shape who gets access to shelter, medical care, or legal aid and who is left without. In policy discourse, “legal migration” is often presented as the benevolent alternative to “irregular migration.” But in legal contexts, “legal migration” effectively means labour migration, a pathway designed to funnel migrants into low-paid, precarious jobs.

Once people enter under the label of “legal migrant,” they are quite literally commodified labour valued not as persons with rights and dignity, but as exploitable units of the workforce. This framing is deeply political. It transforms questions of protection, asylum, or social inclusion into market calculations of supply and demand. Under this paradigm, migrants are tokens in labour schemes. Meanwhile, those not admitted via these labour channels are stigmatized as “illegal” or “irregular,” making them more vulnerable to exploitation.

The consequences on the ground are clear: migrants who arrive via legal labour-migration channels often find themselves in irregular conditions anyway: delayed wages, informal contracts, withheld papers, unsafe work sites. Those excluded from the “legal migration” routes are pushed to the margins, forced into smuggling networks or exploitative labour just to survive. The line between “legal” and “irregular” becomes blurred and morally arbitrary.

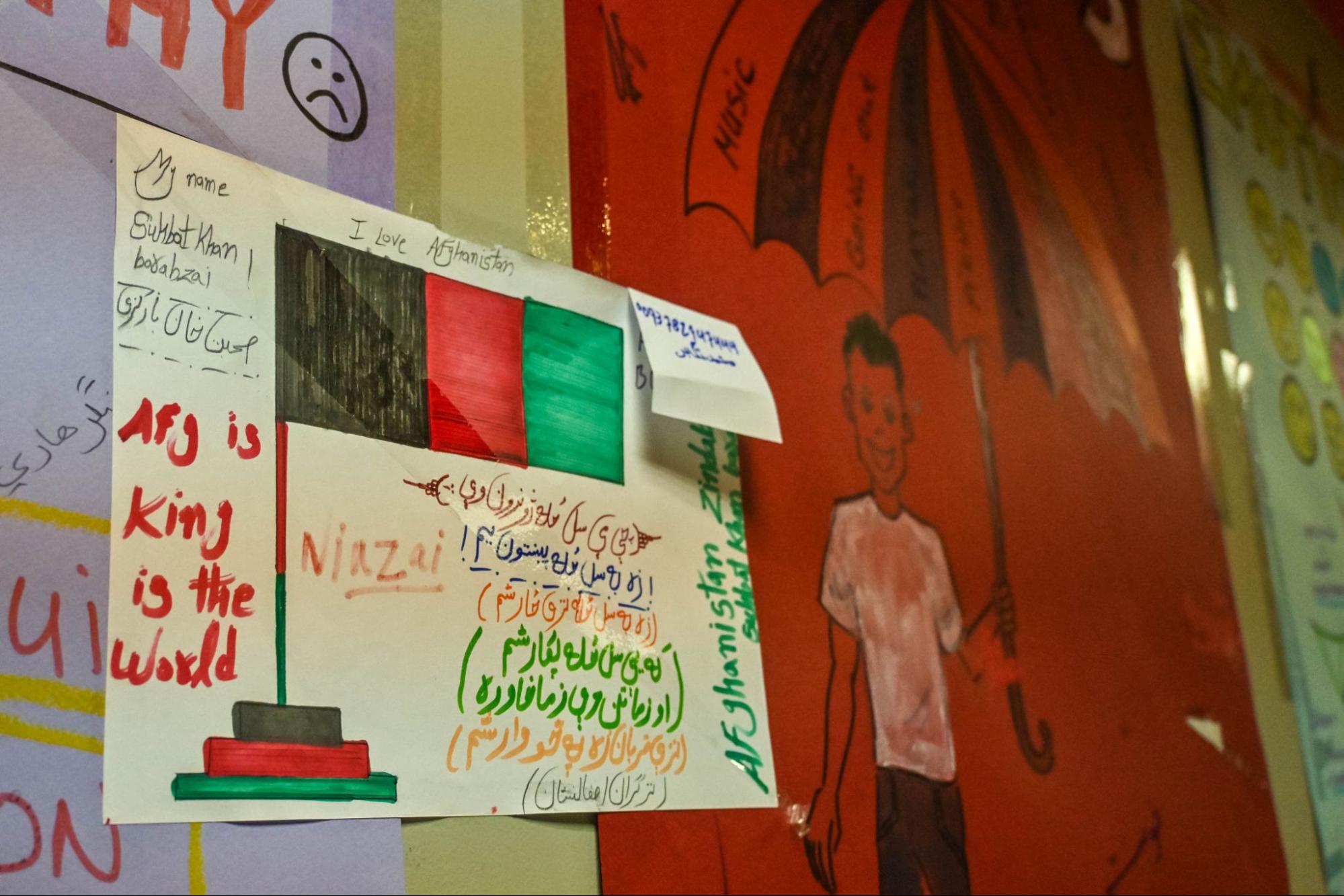

The entrance to Info Park in Belgrade, Serbia. Credit: Lidia Narbona

Serbia as Containment Zone

The new EU Pact on Migration and Asylum will intensify these dynamics. For the Western Balkans, and Serbia in particular, the implications are clear.

First, we expect a general move from tolerated transit to enforced containment: more policing, fast-tracking, and pushbacks, without matching investments in asylum processing, guardianship, and reintegration. The visibility of people on the move will oscillate depending on the level of intervention from authorities: raids will scatter them from their places of living, only for them to regroup days later.

Second, more administration and governance, without protection. Return counselling and 'voluntary' returns programs will be pushed on people as soon as possible, tied to a “duty to cooperate.” Without new budgets to match the increased needs, this risks box-ticking over sustainability.

A picture of the reception centre in Preševo in February 2016. The centre is currently “in standstill”, according to Serbian authorities. Credit: OSCE Parliament Assembly

Third, it is clear that civic space will be squeezed further. As cross-border, inter-governmental collaborations harden, documenting violations or operating shelters will be made more and more difficult just as medical, psychosocial, and child protection needs rise.

Finally, we foresee more digital controls without meaningful safeguards. Biometric border control systems, risk scoring, and “permission to travel” schemes (such as the European Travel Information and Authorisation System, ETIAS) will enter the region without transparent governance or redress, raising questions about data protection and rights.

In Info Park’s hub in Belgrade, we are already seeing an explosion in protection needs as a consequence of the budget cuts in the country. Between February and August 2025, we provided:

● ~200 medical referrals,

● ~500 essential non-food items (shoes, clothes, hygiene kits),

● ~300 hot meals,

● dozens of child protection referrals.

Most new arrivals entered Serbia via Bulgaria, often reporting theft, police violence, and arbitrary detention along the way. Several testimonies describe kidnappings and ransom demands by armed groups in the borderlands. Others point to smugglers charging more for services by bundling transport, housing, and hawala transfers together, or splitting into micro-cells to reduce exposure to the authorities.

For unaccompanied children, the risks are even greater. A 19-year-old Afghan boy we met in July said he had no documents, no relatives in Europe, and feared he was “stateless”. He was determined to reach Germany, but the lack of guardianship or safe accommodation in Serbia left him exposed to trafficking. He joined a smuggling group. According to his testimony: “we know when the police are going to turn a blind eye, you just need to pay the bribe to the right people.”

Inside Info Park’s hub in Belgrade, Serbia. Credit: Lidia Narbona

What Needs to Change

For the group of five at Horgoš, the “route” was not a corridor, but a cycle of detention, transfers, and endless reattempts. Their story embodies the cruelty of Europe’s border regime: a system that contains without protecting, isolates without integrating, and surveils without listening. In Serbia, the so-called “external border” is experienced not as a line of arrival, but as a zone of abandonment where pushbacks, informal removals, and opaque transit arrangements define the everyday.

There is nothing humane or sustainable about this system.

Civil society continues to bear the weight of protection work, often alone, without structural support or political space. While EU policymakers negotiate deals with third countries and reinforce physical infrastructure, the people affected by these choices remain silenced, stuck, or disappeared. The “border” is no longer a line, but a sprawling architecture of denial and deterrence.

We must be clear: border externalisation, like the “migration management” complex it is a part of, is not a neutral administrative tool. It is a political project of exclusion. It cannot be fixed with better monitoring or more audits. Real protection means listening to people on the move, creating spaces for dignity and self-determination, and resisting the machinery that turns migration into a security threat. Until then, the price will continue to be paid not in policy briefings, but in bruises, trauma, and fractured futures, one pushback at a time.

The Border Violence Monitoring Network accepts submissions for its blog. To contribute, please send your submission to press@borderviolence.eu

Thank you for your interest. We look forward to your contribution!