The UK media: An anti-immigration megaphone

By Emilija Krivosic, Communication team member at BVMN. Published on 4 November 2025.

Credits for header image: kimba

On Saturday 13th September, Britain witnessed one of its largest far-right rallies in recent history. According to the news network Al Jazeera, over 110,000 people stormed the streets of London, united in their disdain for the asylum-seeking population in the country. For those following the UK’s current political developments, this rally won’t come as a surprise as the topic of immigration has dominated public discourse in recent years.

Only last year, we saw an estimated 29 anti-immigration riots erupt all over the country from Stockport to Southampton. However, last year counter-protesters dominated the capital outnumbering the far right and deterring a significant turnout. While the most recent rally may not have come as much of a surprise to some, it still begs the question: how did this anti-immigration sentiment gain so much popularity?

A small number of far-right anti-immigration protesters, escorted by police, take an afternoon stroll along Dover's seafront. Photo taken in May 2016. Credits: alisdare

Recent party politics has not only normalised, but better yet encouraged anti-immigrant attitudes in the UK, specifically towards refugees and asylum seekers. Policies such as the Rwanda policy, the ‘Stop the Boats’ slogan and the Illegal Migration Act 2023 are recent examples that have contributed towards the hostile environment.

While it may seem that these have been some of the most drastic and boastful measures towards the anti-immigration ambience, they have succeeded a longstanding campaign of anti-immigration discourse successfully upheld by the British media. A 2016 study by the Migration Observatory found that there was a sharp increase in the volume of newspaper coverage relating to migration since the election of the Conservative-led coalition government in 2010. This increase is significant as the study also observed that the press is good at setting the agenda – telling readers what to think about. Consequently, media coverage has a measurable impact on public perceptions of migration.

It is not only what the media chooses to cover that shapes social reality, it is just as important to observe how it is covered. The word ‘illegal’ has been one of the terms most strongly associated with migrants in UK parliamentary debates over the past 25 years according to the Runnymede Trust’s report. It is in the top five words most strongly associated with the word ‘migrant’. The language used by politicians and parroted by the media reinforces the perception of migrants as unlawful and dehumanises migrants while portraying them as criminals and as a threat. Theresa May’s 2012 declaration to “create a hostile environment for illegal immigrants”, subsequently causing media coverage containing hostile rhetoric around migration and migrants to more than double (a 137% increase), compared to the two years prior, stands in juxtaposition to The United Nations General Assembly, IOM, Council of Europe and European Commission who have all deemed the phrase ‘illegal immigration’ unacceptable. These words have created negative connotations and hostility towards migrant groups, delegitimising their presence in the UK and often using them as a scapegoat for wider societal issues.

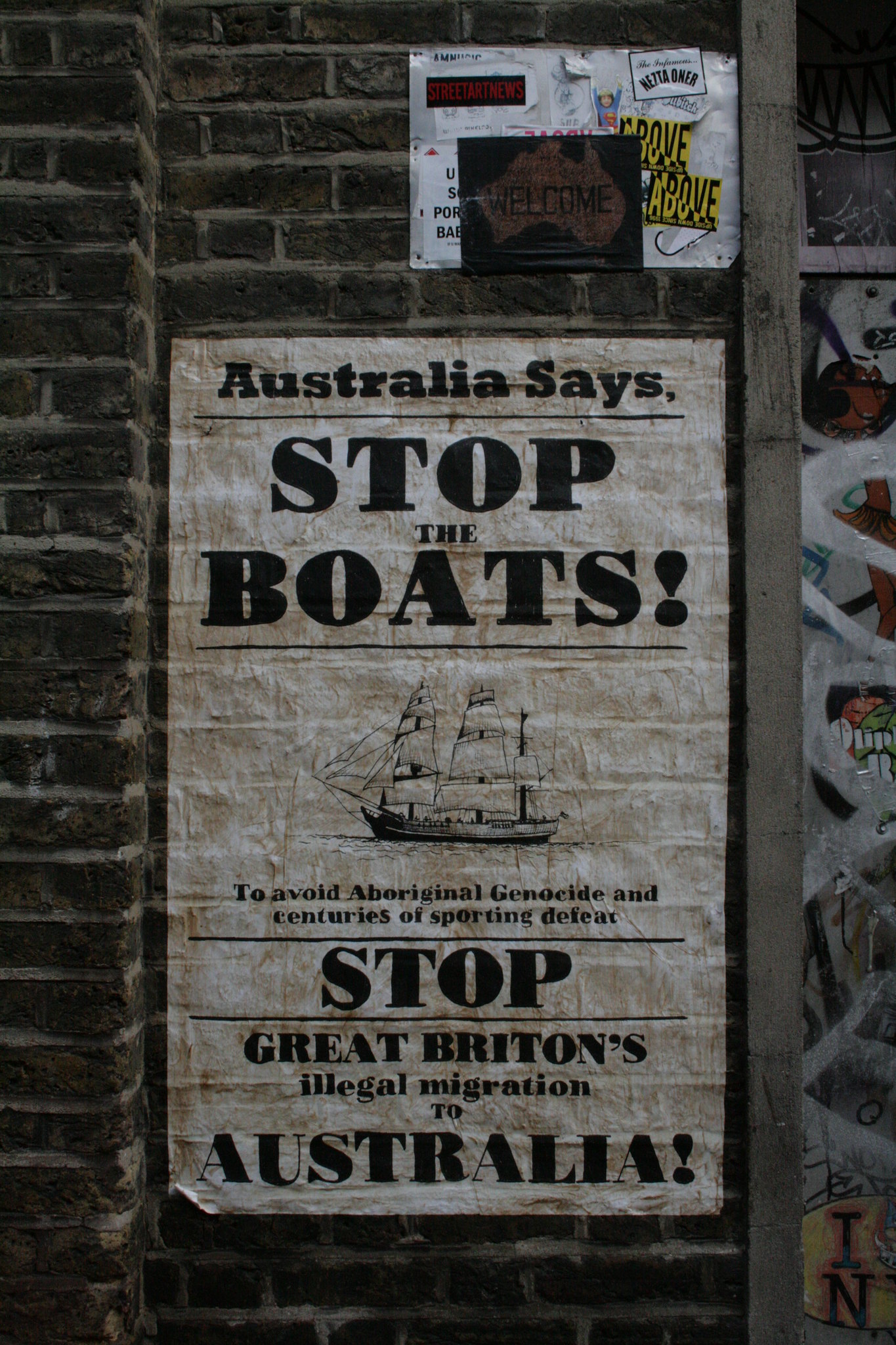

A “Stop Great Britain's illegal migration to Australia” poster, as seen in Tower Hamlets, London, in November 2013. Credits: kylaborg

Terms such as ‘invasion’ and ‘swarm’ that have often been used to describe migrant groups arriving in the UK offer negative connotations and infer large scale and unregulated migration obscuring the empirical evidence. According to the International Rescue Committee, refugees in the UK make up only 0.76% of the population as of June 2025, while asylum seekers made up around 13% of immigrants to the UK in 2024. While these figures have gone up over the last few years, the number remains a very small percentage of the population. Irregular migration is not new to the UK. For years, people have arrived by air without the necessary documents or hidden in lorries or freight vehicles. But what is new is the overwhelming focus of media coverage on small boat crossings. These events are captured on video, reported in the news, and often politicised. This disproportionate emphasis on boat arrivals fuels a sense of crisis and emergency, allowing governments to justify restrictive policies like offshore detention and deportations while neglecting the structural causes of irregular migration. For every article in a left-leaning outlet on migration, there are about 2.5 articles in a right-leaning one. However, even left-leaning and liberal media outlets often reproduce reactionary rhetoric, emphasising enforcement and control over migrants’ rights or structural causes of irregularity. The media visibility and framing of migration and more specifically, small boat crossings, drive public sentiment more powerfully than statistical reality. This “crisis narrative” shapes public opinion, fuels political polarisation, and legitimises restrictive policy responses despite migration being a long-standing and inherent feature of UK society.

By echoing this rhetoric and adopting language that frames migration as a problem to be controlled, Labour risks reinforcing the same dehumanising narratives that have long dominated the political discourse on immigration. This is not the party’s first attempt to appeal to anti-immigration sentiment; the infamous “Controls on Immigration” mugs launched ahead of the 2015 general election serve as a reminder of how such tactics can entrench rather than challenge divisive attitudes.

Now, in government, Labour’s actions, such as pausing family reunion for refugees, extending the qualifying period for permanent residence from five to ten years, and introducing a “one in, one out” approach with France, demonstrate a clear continuation of restrictive policies. Rather than offering an alternative vision, the party appears to be legitimising the fear-driven framing that distorts the national conversation on migration. A more constructive national conversation on migration would require political leadership willing to challenge, rather than exploit, public fears and endorse empathy in its moral arguments. Until that shift occurs, the UK’s migration debate will remain trapped in a cycle of fear, populism, and moral panic. If the media is capable of shaping public sentiment so powerfully, it also carries the responsibility to inform with accuracy and context. Balanced reporting that humanises rather than vilifies migrants could help to reframe the public debate, not as one of crisis and control, but of shared humanity.

Photo taken at the Say No to Tommy Robinson march and rally in London on Sunday 9th December 2018. Credits: Garry Knight

The media and politics operate symbiotically. Sensationalist coverage provides justification for tougher measures, while governments use crisis rhetoric to project control. The convergence of sensationalist media coverage and restrictive political rhetoric has created a feedback loop in which fear and hostility toward migrants are continually reinforced. As far-right movements gain visibility and legitimacy, mainstream parties feel pressured to adopt tougher stances, which in turn validates extremist narratives. This cycle not only erodes the UK’s tradition of asylum and refuge but also corrodes democratic debate, reducing complex social and economic issues to matters of border control and exclusion. To break this cycle, the national conversation on migration must be grounded in facts, empathy, and understanding, values that reflect the reality of migration rather than the fears that distort it.

The Border Violence Monitoring Network accepts submissions for its blog. To contribute, please send your submission to press@borderviolence.eu

Thank you for your interest. We look forward to your contribution!