Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing: How the EU’s New Pact Undermines the Protection of Unaccompanied Minors — Lessons from Malta

By David Silber, M.A. International Social Work. Published on 21 January 2026.

Credit header image: aditus foundation

The New Pact on Migration and Asylum has been presented as a long-awaited modernization of Europe’s asylum governance — a framework that promises faster procedures, clearer responsibilities, and stronger safeguards for Unaccompanied Minors (UAMs). Yet, this promise is misleading.

On paper, the small country of Malta already upholds many of the child-protection safeguards that the Pact now codifies. However, my research on Malta’s age assessment procedure - based on in-depth interviews with practitioners working across asylum and detention - shows something profoundly different. Despite existing safeguards, Malta routinely disregards the presumption of minority, detains children, and subjects them to unreliable and opaque assessments.

The age assessment procedure is the linchpin that determines whether children will actually benefit from the Pact’s safeguards. As long as this mechanism is embedded in a system oriented toward deterrence and border control, those safeguards remain largely symbolic. Malta offers an early warning for a system in which children’s rights depend entirely on whether the state chooses to see them as children, and in which age assessment becomes not a protective tool, but a gatekeeper to exclusion.

In this sense, the New Pact is a wolf in sheep’s clothing: a protective narrative that conceals a framework designed around border control.

The New Pact’s promise: safeguards for children

Before turning to Malta, it is important to understand what the Pact claims to guarantee. The reform introduces a set of child-specific safeguards, many of which mirror existing obligations under EU and international law, such as the best interests of the child as the primary consideration (Article 22 of the Asylum Procedures Regulation (APR)). On paper, these provisions suggest a protective framework for UAMs, particularly in high-risk settings such as border procedures.

A central component of the Pact is the new Screening Regulation, which requires all arrivals to undergo a pre-entry screening of up to seven days in closed facilities. During this phase, states must check identity, health and security risks, and are also expected to identify vulnerabilities, including indicators that someone may be a child. In theory, this early screening is meant to ensure swift protection. In practice, however, carrying out vulnerability assessments in a closed, pre-entry setting where contact with independent actors is limited by design raises serious doubts about whether vulnerabilities can be meaningfully identified at all.

A key safeguard for UAMs is the exemption from the Asylum Border Procedure (Art. 53 of the APR). This procedure keeps certain applicants near the external borders often in closed, detention-like facilities for up to twelve weeks, with possible extensions during appeals (Art. 52). It applies in particular to individuals coming from countries with an EU-wide protection recognition rate of 20% or lower. Additionally, Member States are permitted to place applicants in a border procedure if they have passed through a so-called safe third country, such as Turkey (Art. 43(1) in conjunction with Art. 38(1)(b)). Although physically present in the Member State, applicants are treated under the legal fiction of “non-entry”, enabling restrictions that would otherwise be unlawful.

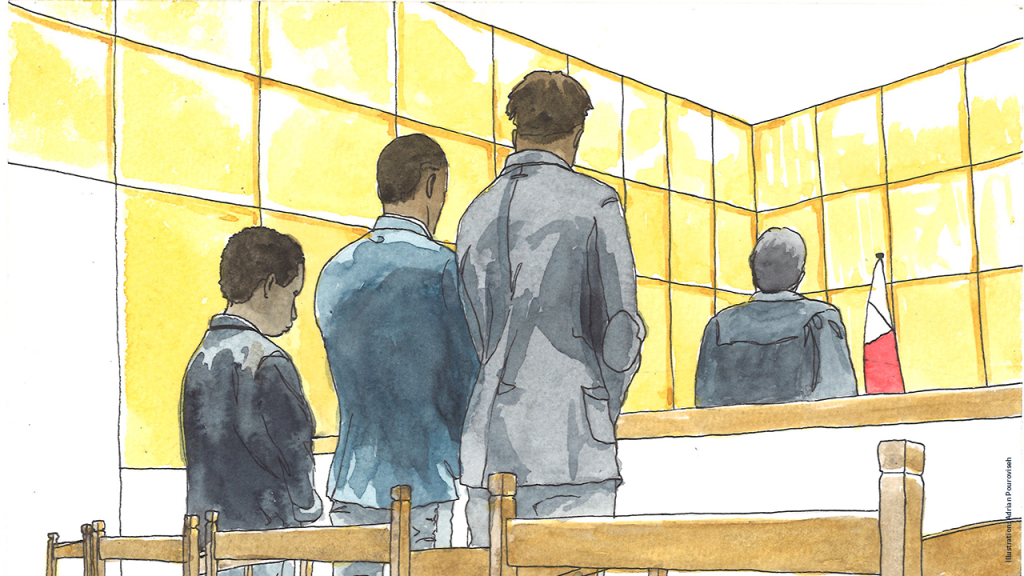

Formally, UAMs are shielded from this system. However, the exemption does not apply to those whom authorities claim to pose a threat to national security (Art. 42(3)(b) and Art. 53(1)(b)). How such risks can be reliably assessed in the chaotic conditions of the EU’s external borders remains unclear. This instead opens the door to arbitrary and discriminatory interpretations. In fact, children in exploitative situations, including those used by organised criminal groups, are often categorised as security risks rather than recognised as victims of trafficking and individuals requiring special protection. This is most evident in the ongoing El Hiblu 3 case in Malta, in which three young African migrants were charged with terrorism after acting as mediators during a sea rescue in 2019.

El Hiblu 3. Credit: Alarmphone

Additionally, it is crucial to understand that the effectiveness of all safeguards depends on children being recognised as such. While this may seem obvious given the importance in setting the decision between protection and detention, it is worth taking a very close look at the wording of the law.

Age assessment: the gatekeeper to protection

If there is doubt as to whether a person is an adult or a minor, Article 25 of the APR introduces a two-step age assessment process. The first step is a multidisciplinary evaluation - including psychosocial assessments, interviews, and visual checks - conducted by professionals with expertise in child development. Only if this step is inconclusive may authorities request a medical examination as a last resort. Medical methods must begin with the least invasive techniques, and if uncertainty persists, the individual must be treated as a minor (under the so-called benefit of the doubt principle, laid out in Recital 37 of the APR).

The Pact thus describes the age assessment procedure as a balanced, multidisciplinary, child-friendly process. But these principles overlook the actual conditions at Europe’s external borders. Border environments are not neutral. They are spaces shaped by time pressure, securitisation, bureaucratic overload, and political incentives to reduce recognition rates. When age assessment is embedded in those spaces, it inevitably becomes distorted by them.

Based on my own research in Malta, visual assessments reward stereotypical assumptions about “adult-looking” boys from certain regions. Psychosocial impressions become unreliable when a child is traumatised, sleep-deprived, or afraid of authority. And medical tests, even when framed as a “last resort”, retain an aura of scientific authority despite wide error margins and deeply contested validity.

What the Pact ultimately creates is a procedure designed for ambiguity. If the outcome is incorrect, i.e. a child is misclassified as an adult, the consequences unfold predictably and brutally: detention, accelerated procedures, reduced safeguards, removal.

Hal Far detention Centre in Malta. Credit: Dougald Hine

Malta: the future that Europe is adopting

Malta demonstrates how fragile child-protection safeguards become when they are placed inside a system structured around deterrence. For years, Malta has maintained the legal fiction that minors should not be detained, that the benefit of the doubt applies, that medical tests are used cautiously, and that psychosocial methods guide the process. Yet in practice, the opposite routinely occurs.

Upon disembarkation, children whose minority is not immediately “obvious” are treated as adults from the outset. That means that they get immediately detained and are held in detention facilities under restrictive conditions, often together with adults, until their minority is officially proven. This reversal of the presumption of minority leads to the situation where many minors are initially detained, as the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) just recently confirmed again.

Credit: aditus foundation

In the meantime, children whose age is disputed are effectively isolated. In Malta, lawyers can only meet them under surveillance, psychosocial and mental-health professionals are denied entry to the centres, and phones are often switched off for the first weeks.

The age assessment itself is highly unreliable. From the outset, it is based on subjective parameters such as a person's appearance, behaviour, knowledge of Western norms regarding age, etc. This begins immediately after disembarkation and continues throughout the entire procedure. Not only do numerous reports from other countries confirm the inaccuracy of age assessment procedures in general, but participants in the study also confirmed this for Malta, where the results of the assessments appear to be partly coincidental. Moreover, Malta regularly relies on bone tests despite its well-known inaccuracy.

If the age assessment determines that the person is an adult, the affected individual has three days to appeal. In this process, the appeal system itself becomes a tool of prolonged detention. Appeals drag on for months while children remain locked up until the process is completed. Several minors were only recognised as children after eight months, during which they did not have access to psychosocial support, schooling, or to child-friendly activities. What should be a safeguard becomes a slow-moving procedure keeping children locked in legal limbo, contradicting the requirement that detention be used only for the shortest appropriate period. In practice, the very possibility of appeal offers no protection at all; it merely extends the time children spend waiting for the system to acknowledge what they declared from day one: that they are, in fact, minors.

Additionally, Malta shows how quickly child-protection collapses when the same institution is in a dual role: the Agency for the Welfare of Asylum Seekers acts simultaneously as a legal guardian as well as the age assessor, meaning children are effectively represented by the very same authority depriving them of their liberty. This structural dissonance erodes trust, denies genuine advocacy, and violates basic principles of independence. Practitioners have described situations where children must “appeal against their own guardians,” a contradiction that speaks for itself.

Finally, Malta shows that detention during age assessment is not a neutral administrative measure but part of a wider deterrence logic that targets children directly. Interviewees described racist and degrading treatment, from mocking minors with cartoons to punishing them for claiming to be under 18,with no independent oversight and no safe way to report abuse. In this system, children are treated not as rights-holders but as subjects to control. These dynamics are not unique to Malta but reflect a broader European trend in which suspicion, punishment, and racialised assumptions overshadow child rights. The European Court of Human Rights has also punished Malta for its unacceptable treatment of individuals who claim to be minors.

The EU is about to codify Malta’s failures

Malta shows us what happens when age assessment is allowed to operate inside a system that prioritises deterrence over protection: safeguards lose their meaning. In a context where only so-called vulnerable groups are exempt from automatic deprivation of liberty, age becomes the most important determining criterion for access to rights. This structural focus on age inevitably generates suspicion: if vulnerability provides release, then claiming minority is easily framed as manipulation. Within this logic, the presumption of adulthood becomes institutionalised, and the system turns against those it should protect. What emerges is a circular structure. Detention produces the need for age assessment, and age assessment in turn justifies continued detention. And the New Pact, despite its child-friendly vocabulary, risks exporting this model to the entire EU.

Photo taken in February 2024. Credit: aditus foundation

The Screening Regulation compresses identity, vulnerability and age checks into a seven-day window inside closed facilities — a timeframe so restrictive that independent actors cannot intervene in any meaningful way. The legal fiction of non-entry creates an environment where children are physically confined but legally invisible, mirroring the opaque first weeks in Malta in which phones are cut, access is blocked and rights exist only on paper. The APR adds technical detail but no procedural clarity on what happens to children while their age is still in dispute. It does not establish deadlines. It does not guarantee guardianship for those not yet recognised as minors. And it contains no explicit right to appeal negative age assessments.

What the Pact calls “efficiency” is, in practice, a system that removes the very actors who could hold states accountable. Without independent guardians, without access to lawyers and social workers, without appeal mechanisms, without oversight, the central promise of protection becomes illusory. The risks are structural, not incidental. A procedure that is ambiguous by design will always default toward exclusion when placed in a securitised environment.

Malta is not an outlier in this sense. It is a preview. Its system shows how easily child-rights obligations are neutralised when age assessment becomes the gatekeeper to protection. The Pact threatens to replicate this logic across Europe: a framework that speaks the language of child protection while creating conditions that make violations predictable and difficult to challenge.

If the EU is serious about safeguarding children, it must confront the core problem rather than polish its procedural surface. Age assessment cannot remain embedded in border enforcement structures, and the presumption of minority cannot be reversed in practice while being celebrated in law.

Beyond this, the situation on the ground invites a more fundamental reflection on the legitimacy of immigration detention itself. If the deprivation of liberty is incompatible with the protection owed to a 17-year-old, it is worth asking why it should suddenly become acceptable the day after that person turns 18. The arbitrary distinction between minors and adults obscures the shared vulnerability of those who have fled war, persecution, and deprivation, and exposes the moral inconsistency of current border practices.

Europe frames the New Pact as a fresh start. But unless its foundations are changed, it risks becoming exactly what Malta already represents: a system in which children’s rights are acknowledged rhetorically but denied in reality — a failure disguised as a safeguard.

The Border Violence Monitoring Network accepts submissions for its blog. To contribute, please send your submission to press@borderviolence.eu

Thank you for your interest. We look forward to your contribution!